Under the Hood

The goal of this software is to enable approximate inference of the phylogenetic history of a distributed digital population solely through analysis of heritable genome annotations — no centralized tracking system required. Here, we will discuss the underlying hereditary stratigraphy methodology that the hstrat library uses within HereditaryStratigraphicColumn objects to provide this capability.

Naive Approach: Bitstring Drift

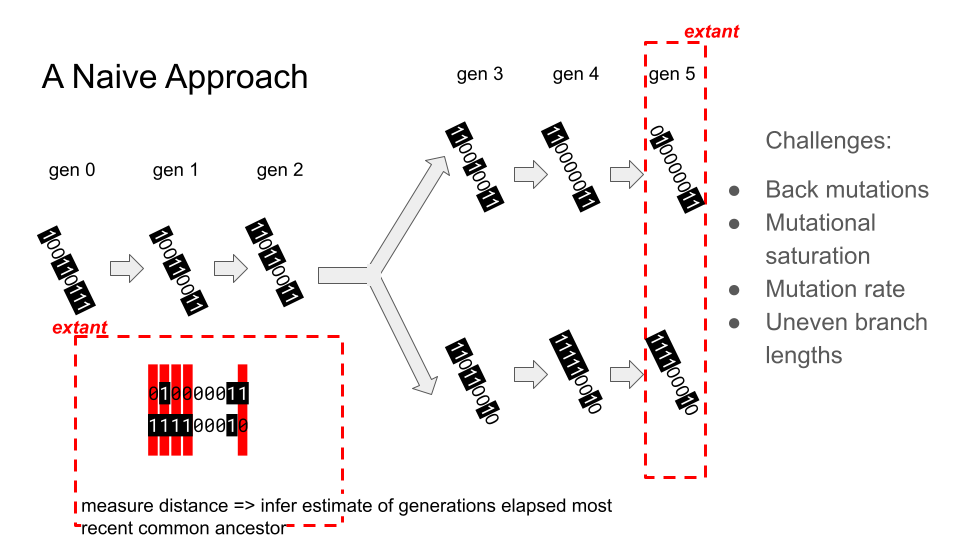

Cartoon showing relatedness estimation via a bitstring under neutral drift

A simple heritable annotation to enable relatedness estimation would be a bitstring under neutral drift. Under this model, the number of generations elapsed since two bitstrings’ MRCA would be inferred from the number of mismatching sites — more mismatching sites would imply less relatedness. An example scenario is shown above.

This model suffers from several serious drawbacks in application as a tool for relatedness estimation, including difficulty discerning uneven elapse of generations since MRCA and difficulty parameterizing the model for effective inference over greatly varying generational scales.

hstrat Approach: Generational Fingerprints

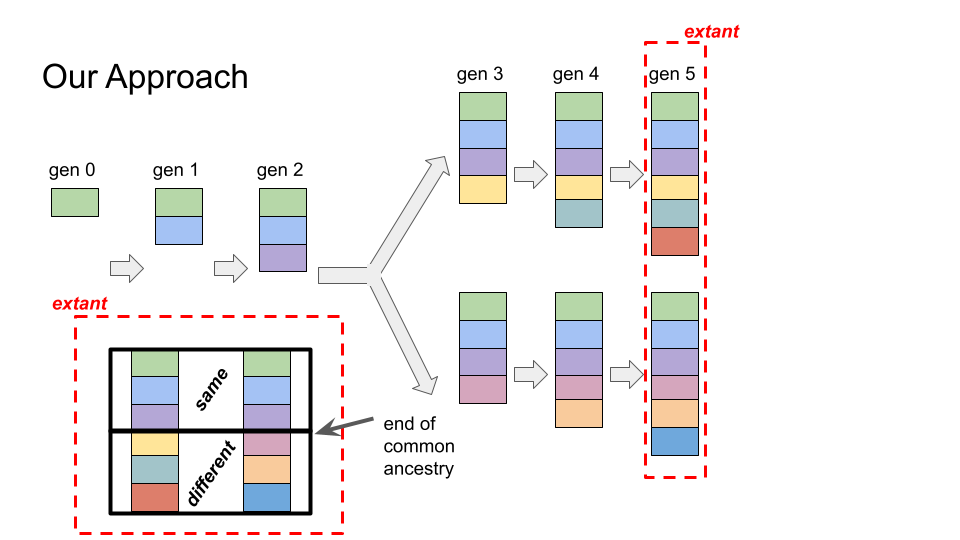

Cartoon showing relatedness estimation via a hereditary stratigraphic column

Instead, we use randomly-generated binary “fingerprints” as a record of shared ancestry at a particular generation.

An example scenario is shown above. Each generation, a new randomly-generated “fingerprint” (drawn as a solid-colored rectangle above) is appended to the genome annotation. Genomes’ annotations will share identical fingerprints for the generations they experienced shared ancestry. Estimation of the MRCA generation is straightforward: the first mismatching fingerprints denote the end of common ancestry.

Internally, we refer to these “fingerprints” as differentia. The bit width of differentiae controls the probability of spurious collision events (where strata happen to share the same randomly-generated value by chance), and is tunable by the end user.

In analogy to geological layering, we refer to the data deposited each generation (differentia and optional user-defined arbitrary annotations) as a stratum. We call the annotation comprised of strata deposited at each generation a hereditary stratigraphic column. In accordance, we describe this general approach for relatedness estimation hereditary stratigraphy.

Pruning Strata

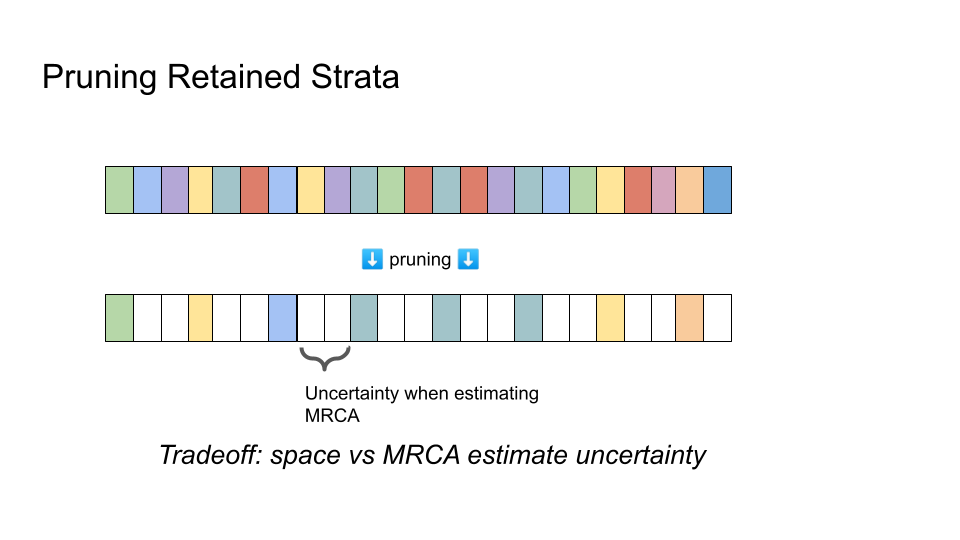

Comparison of hereditary stratigraphic column before and after pruning retained strata

As stated so far, hereditary stratigraphy suffers from a major pitfall: linear space complexity of the annotation with respect to the number of generations elapsed. This means that time required to copy and transmit annotations, as well as memory requirements to store those annotations, will grow rapidly and without bound.

Systematically pruning strata — deleting data from certain generations from the annotation as generations elapse — can reduce space complexity. However, pruning introduces uncertainty to MRCA generation estimates. The exact last generation of common ancestry is bounded between the last-matching and first-mismatching strata, but cannot be resolved within that window.

Stratum Retention Policy

Stratum pruning operations expose a direct, well-delimited, and flexible trade-off between space complexity and estimation accuracy. A pruning strategy must specify the set of strata to be pruned at each generational step. We call the particular sequence of strata sets pruned at each generation a stratum retention policy.

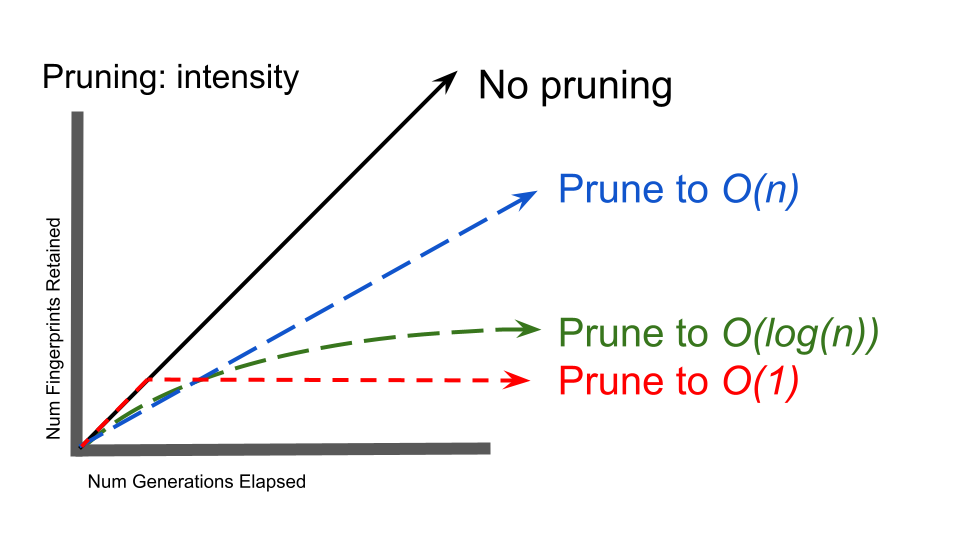

Comparison of column size trajectories under stratum retention policies with different space complexities

The most obvious consideration with respect to stratum retention policy is the number of strata to prune. If, on average, one stratum is pruned for each added then a constant O(1) space complexity will be achieved. On the other hand, pruning no strata or pruning every other, every third, etc. strata will yield a linear O(n) space complexity. Intermediate space complexities, such as O(log(n)), can also be achieved.

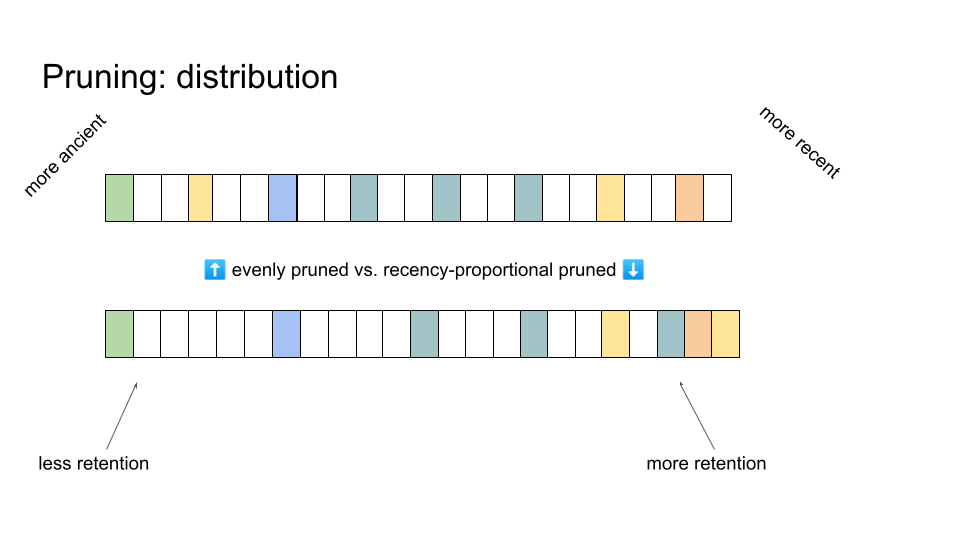

Comparison of even pruning and recency-proportional pruning

Another, more subtle, stratum retention policy consideration is where to prune. An obvious choice might be to prune uniformly, yielding evenly-spaced retained strata. However, pruning may also be performed to distribute retained strata so that estimation windows provide fixed relative error rather than absolute error. That is, error in MRCA generation estimation would be proportional to the number of generations elapsed since the true MRCA generation. Such a strategy exchanges lower absolute error in estimating more recent MRCA events for higher absolute error in estimating more ancient MRCA events. The cartoon above contrasts retained strata under even and recency-proportional pruning.

Requirements on acceptable space-vs-resolution and distribution-of-resolution trade-offs will vary fundamentally between use cases. So, the hstrat software accommodates modular, interchangeable specification of stratum retention policy. We provide a library of predefined “stratum retention algorithms,” summarized here. However, end users can also use custom stratum retention algorithms defined within their own codebases outside the library, if needed. (Any custom algorithms with general appeal are welcome to be contributed back to the hstrat library!)

Further Reading

More detail on the rationale, implementation details, and performance guarantees of hereditary stratigraphy can be found in our publication introducing the methodology,